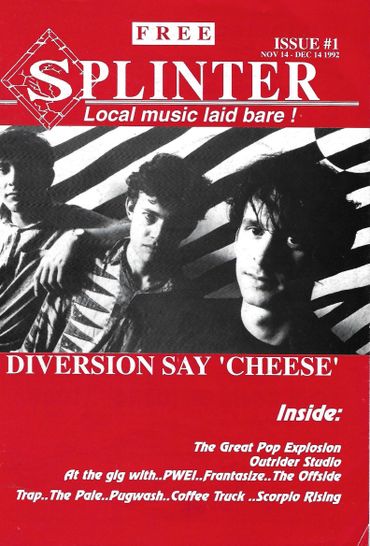

SPLINTER MAGAZINE

What was it?

Splinter was an independent music magazine that existed between late 1992 to sometime in 1994 – a little shy of two years, all told. It was given away free in shops and at music venues, with its print costs paid for by advertising. The magazine initially focused on music in Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire but, as time went on, it concentrated more and more on the latter area, particularly Northampton, which was then going through a very exciting period musically, coinciding with the end of Grunge and the rise of Britpop that followed.

A typical issue would feature news pages, reviews, a gig guide, demo and CD reviews, plus interviews with local and national bands. There was also a letters page full of lively debate in which bands and musicians we’d said mean things about would write in and accuse us of “having favourites” and “only giving our mates good reviews”. Oh, how we laughed.

My background was in fanzines and radio. I did a fanzine called KOOKS! (after the Bowie song) in the early 1980s. It was a pop culture mag, mostly focusing on comic-books, music and film. After that I was a presenter on BBC Radio Northampton's Sunday night ‘yoof show’ The Team, on which we regularly got away with playing the Butthole Surfers and Schooly D. Following that, I’d gone to university, been in a terrible local band, hadn’t got a job, and was at a loose end before Splinter came along.

The magazine's origins

Kevin Bonfield was Splinter's original editor. He lived in Bedford and got together with some friends with the aim of producing a magazine about the local music scene. He came up with the name Splinter too, I think, and had quite ambitious ideas for the project, such as financing it via advertising revenue from local venues and shops. At around the same time I’d decided to produce my own Northampton-based music fanzine, although its action plan was far humbler than what Kev wanted to do with Splinter.

I contacted Stuart Flint, who was the manager of a Northampton band called Diversion, to see if they might be interested in being interviewed for my putative mag, but he told me about Splinter and was responsible for bringing the two different ideas together.

In truth, Kev and his Bedford crew brought a lot more to the party than I did, including a bloke who not only owned a computer and a desktop publishing program but also knew how to use them! I could write a bit and knew a few Northampton bands – some from my time on ‘The Team’ radio show – but that was about the limit of my talent and resources.

Change of editor

Bonfield was editor for the first four issues but had a major falling out with several members of the Splinter staff over a matter in his private life that was absolutely no one's business but his own. I won’t go into details but the entire thing was thoroughly bizarre, especially in hindsight. Kev was the only person on the staff who really knew anything about the Bedford music scene and worked bloody hard doing interviews and reviews. His sudden departure made covering the Bedford scene far harder from then on, although Kev did come back as a writer once the dust had settled.

I was not one of those who fell out with him but did replace him as editor. Someone had to do it and, I suspect, the whole thing would have gone tits up if it been left to the rest of them. Kev was Splinter’s great unsung hero – the magazine was his idea, he did a lot of the groundwork to get it moving, and was then chucked out on his ear.

Under my editorship, Splinter became a far more Northampton-focused magazine. I didn’t drive at the time and had little interest in venturing out to Bedford to see their unappetising array of hair-metal bands. This caused problems because the magazine was put together over there. Somehow, we muddled through, even though Splinter’s Bedford coverage dwindled. The situation would eventually have come to a head, I imagine, but Splinter ended before we got to that point.

Weekends in Bedford

The magazine was put together in a house in Bedford. Reviews and interviews would all be written and collated and then our computer guy (who for reasons I can’t recall was nicknamed ‘Dangerous Dave’) would sit patiently moving copy and photos around on his monitor while the rest of us argued about it.

These page-making sessions at Dave’s would go on ALL weekend. We’d start on a Saturday morning or early afternoon, work into the early hours of Sunday and then pick up the following morning. We usually had between 16 and 24 pages to design (including a cover and gig guide) and I’d often sleep over in Bedford to get as early a start as possible the next day. These sessions were stressful and sleep-deprived, fuelled by booze and Dave’s musical obsessions (They Might Be Giants (who I loathed) and Julian Cope). When the issue was finished, I’d then take it to the printer on the Monday morning. This didn’t always happen, though, because it was bloody difficult getting that amount of material together so quickly.

Deadlines would often slip and we’d sometimes need two weekends to get it all done. Splinter went from a monthly to something that came out whenever we could get ourselves organised to do it. When you aren’t paying people – including yourself – deadlines and professionalism are a luxury.

Dangerous Dave was Splinter's other great unsung hero, giving up his weekends for no reward, out of the goodness of his heart, simply because he wanted to be involved in the magazine.

Bands Good and Terrible

Looking back at old issues of the magazine I’m struck by just how incredibly rude we were about certain bands. We’d think nothing of calling them “shit” and generally being horribly abusive about their demos and gigs. I had a couple of run-ins with disgruntled bands – especially an appalling covers outfit of the time called Tough At The Top – but I’m astonished that I, and other members of the Splinter staff, weren’t physically attacked for some of the scabrous stuff we wrote and published.

I’m also amazed none of the bands we ragged on thought to point out how terrible our spelling and use of grammar was. Worse still, Dangerous Dave had this computer program which meant you could scan copy (reviews, interviews etc) into it and then edit that copy just as you would a regular Word document (this was in the days before email was widely used in the UK). Unfortunately, the scanning software wasn’t always the most accurate so we had issues in which entire pages had letters swapped out – y for g, t for f etc. Because of the tight deadlines, we rarely had the luxury of proofreading everything, so there were terrible typos that I look at now and cringe about. I’m sure we told ourselves at the time that it was all very punk rock. It wasn’t, it was just plain sloppy.

A lot of our reviews seemed to fall into two categories: Band A was fantastic and the best thing we’d heard in years, Band B was rubbish and they should pack it in now. Some of the writing was good but we were all still trying to find our voices as writers and so it was a bit rough and ready, or too heavily influenced by the likes of NME and Melody Maker (especially me).

Splinter's best writer was probably Garrie Fletcher, who now lives in Birmingham. He became notorious for these absolutely eviscerating reviews of bands both local and national. His stuff was hilarious, brutal and deranged. He was our very own version of the NME’s Steven ‘Seething’ Wells (RIP).

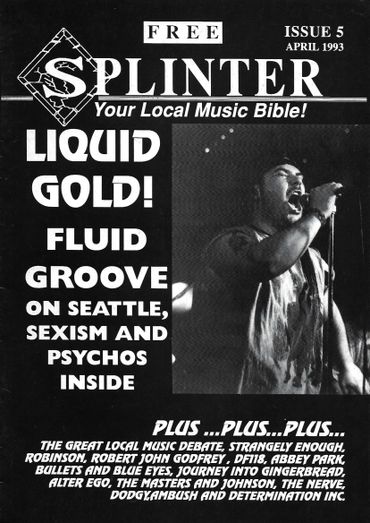

Musically, Northamptonshire was a really exciting place to be in the early ’90s. There was a lot going on all over the place. You had Bullets And Blue Eyes from Rushden, a great rock band called Fluid Groove from Kettering, and a cornucopia of talent from Northampton itself. Diversion were Franz Ferdinand, at least 10 years before Franz Ferdinand. Catfish were Primal Scream's brattish little brothers. Hex were Carter The Unstoppable Sex Machine on better drugs. Shrike were My Bloody Valentine meets T-Rex. Cain were post-Grunge rock gods, and the Offside Trap shucked their initial Madchester obsessions to become a really tight and talented jangly pop outfit. We fully expected some of them to make it – none of them did, more’s the pity.

I even went on tour with Diversion to Czechoslovakia over the Christmas period in 1992. The country was splitting into two separate entities – the Czech Republic and Slovakia – as the chimes rang midnight on 1st January 1993, and we were there, right in the middle of it. The tour was meant to last at least a fortnight but was curtailed after barely a week because, after their gig in a god-forsaken place called Jihlava on New Year’s Eve, the band had all their musical equipment stolen. Thousands-of-pounds worth of stuff. They didn’t have any insurance either so were royally screwed. We had to pool all our cash just to afford petrol for the several-hundred-mile drive home across Europe. It was like something out of Spinal Tap, although not very funny if you were a member of Diversion.

Mistakes

It was a miracle Splinter managed to keep going as long as it did. The idea to fund such a small magazine (print run between 1,000 and 2,000) via advertising was a perfectly viable one and it could have worked but for a couple of flies in the ointment. The first problem was that some people and businesses would book an ad and then not pay for it. One or two you could get away with and write off but, more than that, and you suddenly find yourself with an ever-widening gap between your next print bill and the cash you’ve collected. And that’s what happened – again and again, practically every issue.

Of course, anyone sensible would have had a ‘rainy day’ fund and put out a few issues with fewer pages to save money, but I was young, naive and crap at business, and the thought never occurred to me. I should have tried to get a business manager involved early on, but with no money to pay anyone (all the cash went into the print bills) there was little chance of that.

We ended up owing printers money and defaulting on those payments – not for a month or two but permanently. Somehow, we still found people to print the magazine and it carried on going. I’m really not sure how we got away with it. These days with the Internet and social media, we’d have found ourselves quickly on a blacklist and deservedly so. We were incredibly naive and must have caused the businesses we defaulted on real financial headaches. I really wasn’t cut out to try and run a small business (which Splinter was, pretty much). I was a little more than a dumb kid, who just wanted to write about music without all the other ‘difficult’ stuff.

The move to the Roadmender

We didn't have a ‘proper’ office at first (or at the end, come to think of it). Initially we used my parents’ house as a mailing address and their telephone number as a contact. Eventually, though, we were invited to go and share space with the Northampton Musicians’ Collective at their office in Northampton town centre. (They were in Hazelwood Road, on the top floor of a community centre called Junction 7). It was a real godsend – to have a proper editorial address gave the magazine legitimacy and I liked the NMC and the work they did.

Shortly after, however, we were approached by the Roadmender to up sticks and move in there. There was a guy called David Walker-Collins who ran a company called The Noise Factory. They had the contract to promote gigs at the ’Mender and were based in an office there. He proposed taking Splinter under the Roadmender/Noise Factory’s wing. I’d had it in the back of my mind for a while that I needed to get Splinter set-up for the long-term and that I’d probably move on once that happened. I saw the Roadmender move as a way of securing the magazine’s future – perhaps get some proper funding and structures in place to really get it going properly.

Unfortunately, Walker-Collins or the Roadmender didn’t have any money to spend on Splinter, so the same problems as before persisted. Printers owed money, people failing to pay for their ads etc. We were broke, pretty much, and putting out issues was getting more and more difficult because of it.

Ironically, despite all the problems, the magazine had never been more popular or credible. People trusted us and liked our swaggering style – Oasis were on the rise and we fitted that ‘Up yours, Live Forever’ attitude perfectly. I remember once going into Spinadisc on Abington Street with new copies of the mag and being told by an exasperated assistant how pleased they were to finally have them because he was sick to death of people asking for it all the time!

We didn’t even have our own office at the Roadmender – we’d set-up our stuff in one of the dressing rooms and then take everything down again before every big gig at the venue. I’d often go in the following morning to find our ‘office’ looking like a bomb site, the result of whichever band had played the night before and used the dressing room. It was entirely ridiculous and it's only in hindsight I wonder how the hell I ever put up with it.

First Birthday Bash

We’d co-sponsored and organised gigs under the Splinter banner pretty much since the magazine’s inception. There was one at Esquire’s in Bedford (if memory serves) and several all-dayers at the Old Five Bells in Kingsthorpe.

As our links with the Roadmender and Walker-Collins’ Noise Factory became closer, though, we graduated to something rather more ambitious – a first birthday party for the magazine featuring indie darlings The Family Cat (they did ‘Bring Me The Head Of Michael Portillo’), plus Splinter-approved local bands Wishplants, Bullets And Blue Eyes, President Bush (pictured above left), and Catfish. If memory serves, the event was Walker-Collins' brainchild and he did us proud.

Splinter’s First Birthday Bash (as it was christened) took place in the Roadmender’s main hall on Thursday, November 4th 1993 and was a massive success. It was the point at which I thought to myself, “Bloody hell, we seem to be on to something here.”

Splinter vs the Nazis

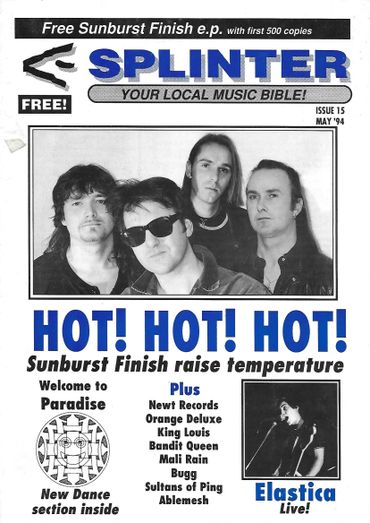

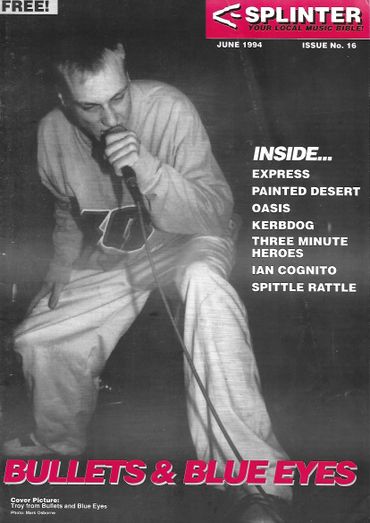

The magazine became more political as time went on, especially around issues of anti-racism and anti-fascism. There was a band from over Rushden way, called Bullets And Blue Eyes, who gigged in Northampton a lot. They reminded me a tiny bit of the Red Hot Chili Peppers but with a brassy British soul edge, like Dexy's. They were fabulous – great live, terrific frontman, proper songs, the lot. They had a multi-racial line-up and addressed issues around racism in their songs and interviews. We stuck them on the cover and pretty much told anyone who’d listen they were the best thing since sliced bread. Along with Diversion, I guess they were the quintessential Splinter band.

Our enthusiasm for BABE brought us to the attention of local racists (BNP and Combat 18). I got a threatening letter (above, left) and started getting threatening phone calls too (all anonymous, naturally). The police became involved, but there wasn’t much they could do. I remember them suggesting we tone it down a bit but I did the opposite instead – organised a multi-band benefit for the Anti-Nazi League in the back room of The Racehorse pub.

BABE were meant to headline, but had to pull out when the threats to their manager from Combat 18 got too serious to ignore. The gig went ahead with local bands including Mystic Crew and Hex, and was a huge success – the place was absolutely rammed and we made a lot of cash for the ANL’s local branch. I don’t think I ever heard from the Nazis again (perhaps our sudden move to the Roadmender threw them off the scent).

The end

Having been unemployed for almost my entire adult life, I was eventually forced on to one of those week-long Restart courses by the Job Centre. It ended up being a blessing in disguise, and confirmed some of the things I’d been thinking about for a while – I wanted a proper job in journalism with proper money and was never going to get either sticking with Splinter. That on top of the Nazi harassment and a couple of unsavoury incidents involving disgruntled local bands had made up my mind to chuck it in.

I’d been doing Splinter for two years and although it had been successful, I was still living hand-to-mouth. It was time to get out. I applied for and was accepted on to a journalism course down in Mitcham and left Northampton never to return (at least not permanently) soon after.

Walker-Collins found some guy to replace me as editor (whose name I don’t recall) and I think they did one more issue – a massively slimmed-down leaflet of only a few pages. It disappeared without trace soon after. A great shame as, at the height of its powers, Splinter was very popular and certainly did a lot for the area’s music scene.

And one more thing... If anyone reading this still has any Splinter memorabilia (tickets to the Roadmender gigs, flyers etc), please scan it and email it over to me. I'd love to add it to this article.

Have Guitars... Will Travel

Some of the above appears in an abbreviated/rewritten form in the book, Have Guitars... Will Travel Vol.4 A Journey Through The Music Scene in Northampton 1988-96 by Derrick A. Thompson (Whyte Tiger Publications 2018).

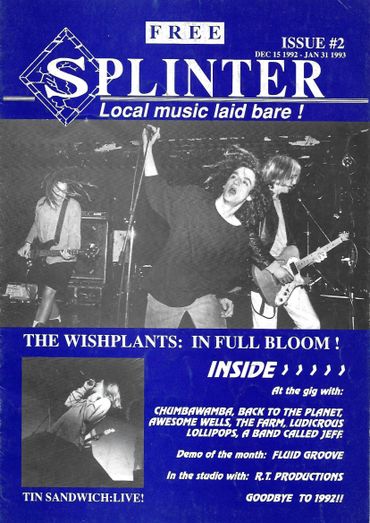

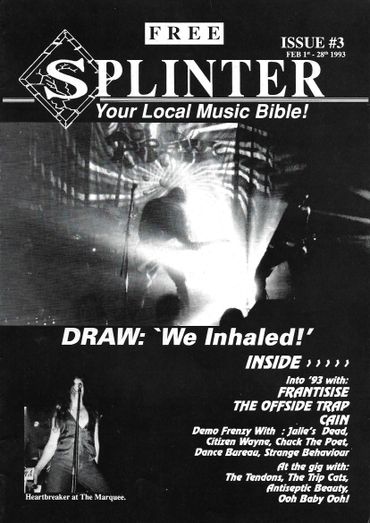

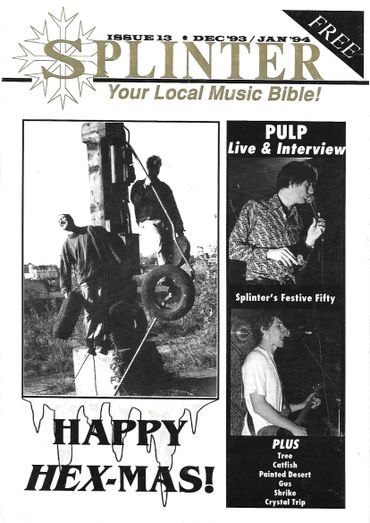

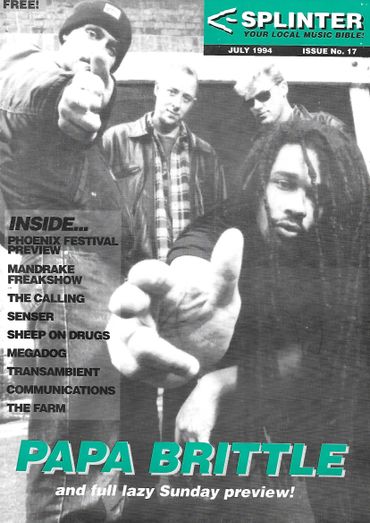

Splinter Cover Gallery

Copyright © 2018 Andy Winter All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy